Summary of Kidney Cancer Take-Home Messages from ASCO GU 2020

Source: International Kidney Cancer Coalition

Over 4,000 delegates attended the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary (GU) Cancers Symposium in San Francisco, 13-15 February 2020. The International Kidney Cancer Coalition (IKCC) was present with a booth to raise awareness, and also attended many of the medical and patient advocacy sessions.

Please note: The following summary was prepared by patient advocates for the benefit of Patient organisations around the world who focus on kidney cancer. While this summary has been medically reviewed, the information contained herein is based upon public data shared at this meeting and is not intended to be exhaustive, or act as medical advice. Patients should speak to their doctor about their own care and treatment.

TALKS

New kid on the block: sitravatinib

Dr Pavlos Msaouel from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA talked about the results from one of the first clinical trials of a combination of a new drug, sitravatinib, with nivolumab in people with advanced kidney cancer that had already been treated.

Sitravatinib is a type of drug called a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), which works by limiting the growth of blood vessels to the tumour. Sitravatinib may also work by making the tissue around the tumour less attractive to cancer cells. Nivolumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor that has been shown to work in kidney cancer. Nivolumab releases the ‘brakes’ on the immune system allowing the immune cells to kill the cancer cells more effectively. Since a combination of these two drugs seems to work well in a few other cancers, like bladder cancer, the researchers thought it might work in kidney cancer as well.

“The way sitravatinib works led us to explore whether the inhibition of these pathways by sitravatinib can induce, enhance or restore responses to immunotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic kidney cancer who had previously progressed on immunotherapy,” Dr Msaouel said. “We used nivolumab as the immunotherapy backbone and tested whether ist combination with sitravatinib would produce good responses in immunotherapy-resistant renal cell carcinoma.”

The main purpose of this study was to see if patients could manage to take the two drugs together. There were 40 kidney cancer patients in this study. The side effects of the combination of sitravatinib and nivolumab appeared manageable. The most common side effect was diarrhoea, but it was not very bad. Four patients stopped treatment because of problems with side effects (only 10% of all patients). Researchers also wanted to find the best dose of sitravatinib for kidney cancer patients, and they found that a pill of 120 mg once a day gave the best results when combined with nivolumab. The researchers are planning a larger follow-up study with this dose of sitravatinib and nivolumab.

Although the results are still very early, the combination of these two drugs showed encouraging benefits for patients with advanced kidney cancer who had already been treated with a TKI (like sunitinib and pazopanib), without too many severe side effects.

Should the original kidney tumour be removed from people with advanced kidney cancer who are taking immunotherapy?

Surgery to remove the kidney tumour is often the preferred treatment for people with kidney cancer that has not spread. Recently, doctors have been questioning whether it is beneficial to operate to remove the kidney tumour in patients with kidney cancer that has already spread beyond the kidney. In most other cancers that have spread, performing this kind of surgery is not recommended. It carries all the risks and downsides of invasive surgery, but generally does not improve survival. Instead, cancer medicines (e.g. tablets, chemotherapy or immunotherapy) have proven more beneficial.

Historically, kidney cancer has been considered an exception. Clinical trials of cytokines, such as interleukin-2 and interferon– alpha, in the late 1990s showed that people with advanced kidney cancer treated with cytokines lived longer if they had surgery to remove the kidney tumour, compared to those who did not.

In the 2000’s, cytokines were largely replaced by targeted therapy for the treatment of advanced kidney cancer. Clinical trials of surgery before and during treatment with targeted therapy clearly showed no benefit of removing the kidney tumour.

A new family of immunotherapies for advanced kidney cancer include drugs such as nivolumab, ipilimumab, avelumab and pembrolizumab. These drugs work by releasing the ‘brakes’ on the immune system allowing the immune system to kill the cancer cells. These immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs are sometimes given in combination with targeted therapies that block the blood supply to the tumour. Many researchers and oncologists have questioned whether the old studies of kidney surgery for people with advanced cancer apply to today’s patients who have access to these new, and sometimes more effective medicines.

At the ASCO GU Cancers Symposium 2020, researchers from a large international research team known as the IMDC used data from people across the world to see whether surgery to remove the kidney tumour improved the lives of people taking immune checkpoint inhibitors.

They found that surgery was associated with improved survival in patients who took immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, the team stressed that these results do not apply to all patients with advanced kidney cancer. People taking immune treatment and surgery together are likely to be younger and have less medical problems. Because this was not a controlled study, these findings should be interpreted as preliminary only. Patients should decide very carefully if they are offered surgery, and in general, cancer medicines should be prioritised.

Radiation is safe, but does not improve immunotherapy in kidney cancer

New medicines for patients with advanced kidney cancer have improved rapidly in recent years, but many people need better outcomes, so research and clinical trials are more important than ever. Immunotherapy is one of these treatments.

Radiation has been used to treat cancer for over a century. Computers now enable radiotherapy to be focused so precisely, that it delivers a very high dose of radiation to a tumour, killing cancer cells but causing less damage to surrounding healthy tissues. Research in the laboratory has suggested that radiation might help immunotherapy by killing Cancer cells and making them more visible to the immune system.

Two clinical trials were presented at the ASCO GU meeting. First was the Phase II NIVES trial. In this trial, advanced kidney cancer patients who had been treated with targeted therapy were treated with the immunotherapy drug nivolumab and focused radiation. Radiation appeared safe with the immunotherapy, but people in the trial did not seem to benefit more than past studies of immunotherapy alone.

The second trial was the RADVAX RCC trial, which combined two immunotherapy drugs (nivolumab and ipilimumab) with focused radiation in patients with advanced kidney cancer. The benefit of adding focused radiation to the two immunotherapy drugs seemed at least equal to past studies of taking the two immunotherapy drugs alone and appeared safe.

Both these clinical trials enrolled small numbers of patients. In both trials, radiation was given to only 1-2 spots of cancer. These trials do not support immediate use of radiation with immunotherapy in people with kidney cancer, but they show that if radiation is needed, it is safe when taking immunotherapy. One situation where this might be useful is if one tumour starts to grow, while other spots of the cancer are shrinking due to immunotherapy treatment; “hunting down tumours that escape” seems like an attractive and sensible idea. Future trials will tell us if there are better ways of improving the benefit of immunotherapy in combination with radiation.

Moving up the chain to HIF-2α to block blood vessels in kidney cancer

Advanced kidney cancer is best treated today with the combination of either two drugs that unleash the immune system (immunotherapy; nivolumab and ipilimumab) or an immunotherapy drug (pembrolizumab or avelumab) plus a tablet that blocks blood supply to cancers (TKI; axitinib). These combinations of treatments help some people, but unfortunately the majority of people do not experience complete disappearance of their cancer. These people need further treatment, and most of the current options are of limited effectiveness.

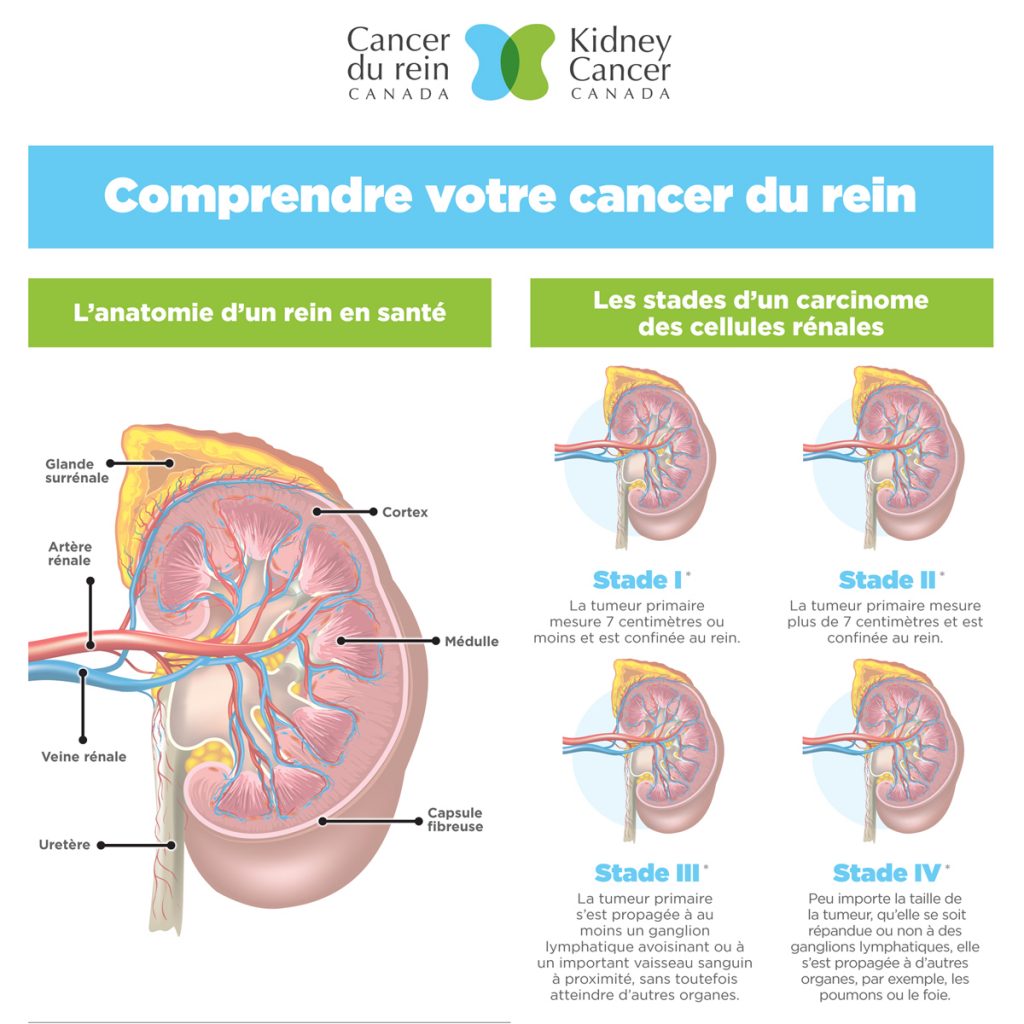

Many kidney cancers (the clear cell type) grow many extra blood vessels. This is often because the machinery that controls blood vessel growth is broken. For the last decade or more we’ve had tablets that work at the end of this chain; tablets that end in -nib like sunitinib and pazopanib.

A new clinical trial was reported at ASCO GU using a new tablet that works further up the chain, closer to the breakdown. This link in the chain is called hypoxia-inducible factor, HIF-2α. A new tablet called MK-6482 blocks the action of HIF-2α. MK-6482 was tested in 55 patients who had taken several previous treatments for kidney cancer; most had taken at least three prior drugs.

In about one-quarter of people, their tumour significantly shrank in size, and in 80% of patients their cancer was controlled and didn’t grow while on treatment. People taking MK-6482 seemed to manage to tolerate the drug; only two people had to stop the treatment because of side effects. This result is promising enough that MK-6482 is being studied in a randomised trial compared against another drug used for kidney cancer; everolimus. If this bigger study is positive, MK-6482 could be a new treatment option for advanced kidney cancer patients who have tried other drug treatments but not been successful. As it seems to be well tolerated, it might also be able to be combined with other treatments like immunotherapy in the future.

POSTERS

Poster 767

Researchers are testing whether adding cabozantinib, a TKI for advanced kidney cancer patients, makes the nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination treatment work better in an ongoing clinical trial called COSMIC-313.

The COSMIC-313 trial was presented in a poster by Professor Toni Choueiri from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, USA. This study is looking for 676 people with advanced kidney cancer who are in poor health or whose cancer is growing fast (those at either intermediate or poor risk on the IMDC scale). The trial is looking for people who have not been treated with anything else before. Patients will be treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab together and then randomly allocated to take either a placebo tablet or cabozantinib. Neither the patient nor the doctor will know if they are receiving placebo or cabozantinib.

For each patient, the researchers will be assessing the time from starting treatment in the trial to when the cancer gets worse (progression-free survival) to determine the success of the trial. Researchers will also record all the side effects in this study to see which treatment is tolerated the best (nivolumab, ipilimumab, cabozantinib or nivolumab, ipilimumab, placebo). The trial is looking for patients now in North America, Europe, the Asia-Pacific region, and Latin America (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03937219).

Poster 623

A scan shows a mass on your kidney – is it cancer? Or something less aggressive? Poster 623 looked at the use of a biopsy; removal of a small piece of the kidney mass with a needle to look at the cells under a microscope to see if they are cancer. The question being asked was whether taking a biopsy reduced over treatment in people found to have a benign, less aggressive mass called an oncocytoma. The researchers followed 170 people with proven oncocytoma. Seventy percent (70%) had been diagnosed using a biopsy and after biopsy almost all people (93.4%) chose to take active surveillance; no surgery, just watch the lump with scans and doctor’s appointments. On average, these oncocytoma grew only 1mm per year, though a quarter of people had growth at a rate >5mm per year. Less than 10% of people chose to have an operation after starting surveillance, and no-one had spread of their cancer. Biopsy reduces the use of unnecessary surgery and its side-effects for benign renal masses, such as oncocytoma. The information from this study gave us further information about oncocytoma and supports the use of active surveillance as a safe Management option, which can reduce the harm caused by over treatment.

Poster 637

Poster 637 reported on a group of patients facing one of the toughest situations; their kidney cancer had spread into the brain. This was a real-world report of 17 patients with advanced kidney cancer in the brain. The patients were treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab combination immunotherapy. For a lot of people, the treatment wasn’t successful. However, some people benefited from combination immunotherapy treatment. Forty-two percent (42%) of people had shrinkage of their tumour (though no-one saw cancers disappear completely) and another 29% had stable disease where their cancer stopped growing. Only about 20% of people did not respond to treatment and their cancer continued to grow. The amount of treatment, and the amount of side-effects was similar to that seen in other clincial trials with the combination immunotherapy treatment. Of note, 50% (3/6) patients treated with this combination after failing to respond to another treatment had tumour shrinkage.

Poster 687

In relation to this, Poster 687 looked at another trial of two drugs called avelumab and axitinib (JAVELIN Renal 101 trial; an immunotherapy and TKI). Some people on this trial had kidney cancer that had spread to the brain, and the combination of drugs might have helped people more than taking a TKI tablet (sunitinib) alone. People with kidney cancer that has spread to the brain still face a very tough path, but these very small reports give some hope that new treatments might even help in this very difficult situation.

Poster 642

Poster 642 presented data from the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) looking at the question of what happens to people if their kidney cancer spreads to specific parts of the body. If a cancer spreads to brain, liver or bones, that is generally a worrying situation in most cancers. Spread of the cancer (metastases) to organs that make hormones (endocrine organs like the pancreas, thyroid, adrenal) are infrequent but this study showed that people with this pattern of spread had the longest median overall survival. The study confirmed what is seen in most cancers; bone, liver and brain metastases were associated with a shorter survival. Understanding these patterns is useful for patient counselling about treatment options and for designing new clinical trials.

Poster 655

Poster 655 used a different database called REMARCC (Registry of MetAstatic RCC) that follows people with advanced kidney cancer. Four hundred and forty seven (447) patients with or without bone metastases were included in the analysis. The authors concluded that presence of bone metastases does not independently predict survival or outcomes in advanced kidney cancer. This is at odds with the IMDC poster above; this is an important area of ongoing study.

Poster 686

Poster 686 reported on a very rare group of people with metastatic fumarate hydratase (FH) deficient renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a rare metabolic variant of RCC. The authors reported on the experiences of 32 patients with FH-RCC showing a distinct pattern of disease course with immediate spread around the kidney into the space between organs inside the abdomen (the peritoneal space). People with FH-RCC had a high chance of response to targeted therapy combinations (e.g. VEGFR/mTOR Inhibitor combinations; lenvantinib + everolimus), but there were limited responses to immune checkpoint inhibitiors, at least when given as a single drug like nivolumab or pembrolizumab.

Poster 707

Finally, Poster 707 reported on a question we would have thought incredible only a few years ago; if you have kidney cancer that has spread from the outset, you take combination immunotherapy and all the cancer spots on your scans completely disappear, and all that remains is the original spot in the kidney… should you then have an operation to remove the primary kidney cancer? Is it worth the risk of an operation to be able to say that the scans are all clear?

This poster reported the challenges of nephrectomy after complete response to immune checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eleven patients who had not had surgery at diagnosis were included in the study. The operations were perhaps more difficult, and one patient died of post-operative complications, but live cancer was still found in most patients. The authors concluded that surgery to remove the primary kidney cancer following combination immunotherapy could allow people to have a “complete response” in selected patients. Due to technical complexity and complication rates, this surgery should be performed in centers with extensive experience. Although only a small number of patients were investigated, this study looked at a new treatment pattern, and more data on surgical safety are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Editor:

Associate Professor Craig Gedye (AU)

Associate Editors:

Professor Axel Bex (NL/UK)

Dr Shaan Dudani (CA)

Dr Chun Loo Gan (CA)

Dr Rachel Giles (NL)

Dr Daniel Heng (CA)

Dr Fernando Maluf (BR)

Dr Francisco Rodríguez-Covarrubias (MX)

Medical Writer:

Dr Sharon Deveson Kell (UK)